Exercise Solutions

Introduction

See the source code on Github Repo, and if you have any questions, feel free to contact me at brycechen1849@gmail.com . It serves mainly as a public note for the book and it’s still being rapidly updated because I’m, at the same time, trying to get familiar with the RL research area.

References

The code implementations references are:

- Solutions to exercise problems (However, this part are somewhat outdated because the latest version of the book has covered a lot of new exercises). Reinforcement-Learning-2nd-Edition-by-Sutton-Exercise-Solutions

- Code for each figure in the book: reinforcement-learning-an-introduction

For figures, usage and examples can be accessed at Matplotlib Gallery

Solutions

Chapter 1

Chapter 1 is an introductory chapter with tic-tac-toe game as an example of the full story. It involves more advanced topics on reinforcement learning that I would choose to implement when later chapters are finished. (Although there is a implementation of the full simulation in tic-tac-toe.py)

-

Exercise 1.1 Self-Play Suppose, instead of playing against a random opponent, the reinforcement learning algorithm described above played against itself, with both sides learning. What do you think would happen in this case? Would it learn a different policy for selecting moves?

Ans:

I guess from intuition that the process would start with both side learning to play better games as both side have no good estimations on each state. As they update their estimations, ties will be more and more common. They will converge to all ties at last.

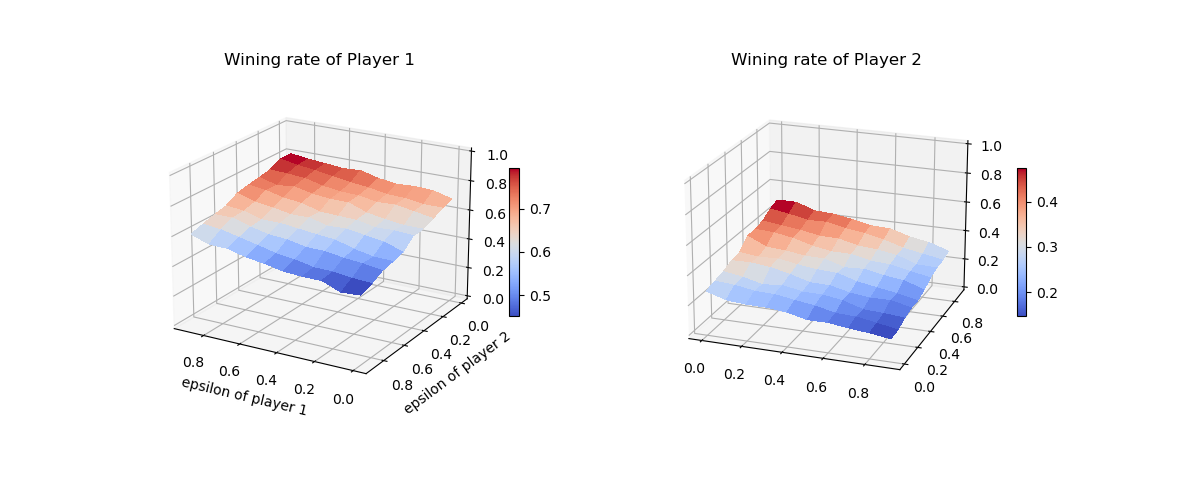

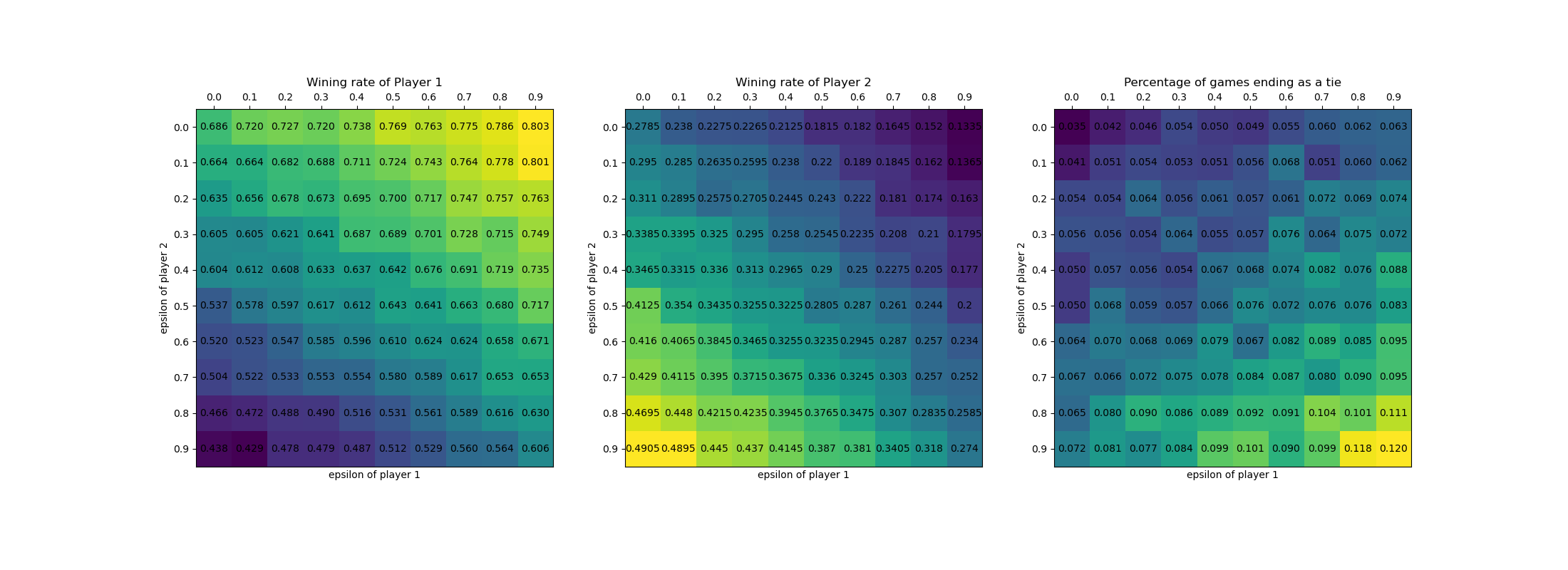

Since the final performance are highly dependent to epsilons. I did the experiments with a grid of epsilons ranging from 0 ~ 0.9. Each set trains for 10,0000 rounds of games and tests on 10,000 rounds of games.

Test results are shown on the figure. Trend is that with higher epsilon a player would have higher winning rate. Opponent’s desire to explore has negative effect on a player’s performance.

-

Exercise 1.2 Symmetries Many tic-tac-toe positions appear different but are really the same because of symmetries. How might we amend the learning process described above to take advantage of this? In what ways would this change improve the learning process? Now think again. Suppose the opponent did not take advantage of symmetries. In that case, should we? Is it true, then, that symmetrically equivalent positions should necessarily have the same value?

Ans: In theory, using symmetries won’t provide any improvement on performance. The only good thing is that it need less memory to store estimations that consists of all possible states. It might even get performance degrade if the opponent do not use symmetries. In that case, players using symmetries would have less information about the state than players that treat them differently, thus the estimations would be less accurate than I should have been.

-

Exercise 1.3 Greedy Play Suppose the reinforcement learning player was greedy, that is, it always played the move that brought it to the position that it rated the best. Might it learn to play better, or worse, than a nongreedy player? What problems might occur?

Ans: Experiment stats:

player 1 epsilon = 1.0, player 2 epsilon = 0.0

trained 10,000 rounds of games and tested 2000 turns

player 1 winning rate is 0.40400, player 2 winning rate is 0.51850Conclusion: This seems kind of conflicts with the conclusion we draw at exercise 1.1, I think it’s because although p2 do not tend to explore, it has passively taken advantage of p1 that is an active explorer, who brought diversity to states that they both experienced.

-

Exercise 1.4 Learning from Exploration Suppose learning updates occurred after all moves, including exploratory moves. If the step-size parameter is appropriately reduced over time (but not the tendency to explore), then the state values would converge to a different set of probabilities. What (conceptually) are the two sets of probabilities computed when we do, and when we do not, learn from exploratory moves? Assuming that we do continue to make exploratory moves, which set of probabilities might be better to learn? Which would result in more wins?

Ans: Implement a new version of the game that (1 updates estimations after each move and (2 learning rate decays. We look at lines that records the learning process of 5 different epsilons with or without updating estimation in exploratory moves.

The CuriousPlayer Implementation

# The original version use greedy[i] indicating if it's a greedy action. # we can just leave it out and directly update the estimations. td_error = (self.estimations[states[i + 1]] - self.estimations[state]) self.estimations[state] += self.step_size * td_errorand in the training function

# Here I use i/epochs to let step_size decay from 0.1 slowly to 0. player1.step_size = 0.1 * (i / epochs) player2.step_size = 0.1 * (i / epochs) player1.backup() player2.backup()The results are

2000 turns, player 1 win 0.67050, player 2 win 0.28600

compared with ex1.1 results

2000 turns, player 1 win 0.686, player 2 win 0.284

Not quite different from the constant step-size version, I guess it affect only the speed of convergence, not the probabilities it converge to. -

Exercise 1.5 Other Improvements Can you think of other ways to improve the reinforce- ment learning player? Can you think of any better way to solve the tic-tac-toe problem as posed?

Ans:

Optimistic Initial Estimations. By assigning 1 to all unfinished states’ estimation, the player is greatly encouraged to explore at the very starting phases.

The figure demonstrates the comparison.